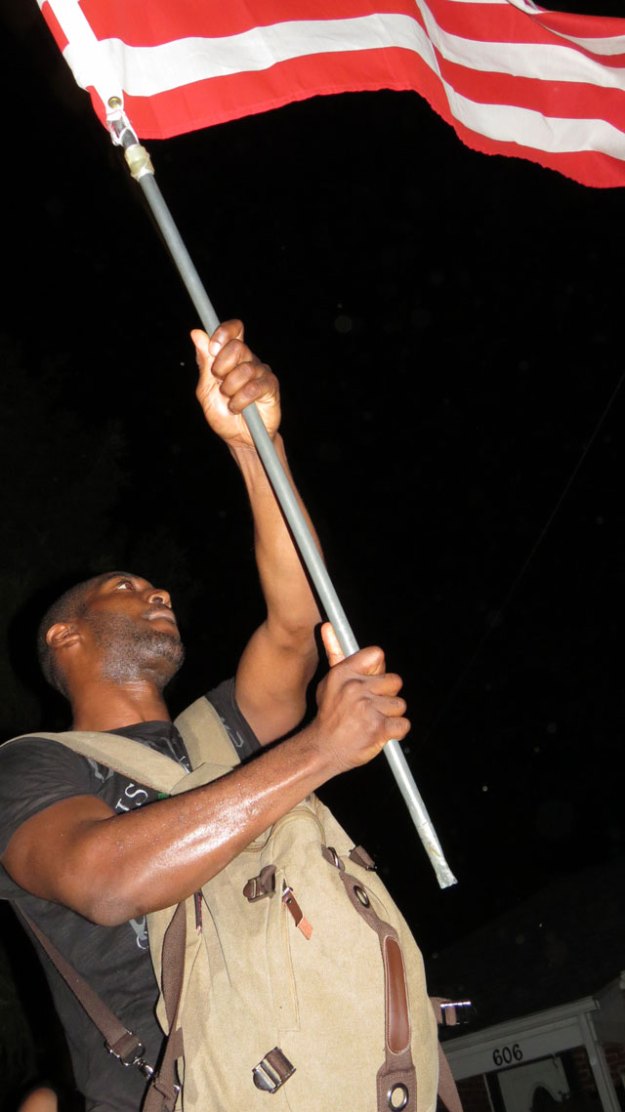

Supporters of Police Officer Darren Wilson gather outside a local bar to greet traffic and raise money for Wilson.

This is the second part of a series on the events in Ferguson called “Healing St. Louis”. Read the others:

• Part 1: Ferguson got their attention

Shirene has been showing up to the protest site since Michael Brown was killed. West Florrisant Avenue at night is at once a ghost town and a bustling people-scape. Storefronts are closed and boarded with plywood. Commerce is scant, but activity is everywhere.

Only one black-owned store was smashed, said Jermell, 27. The rest were saved because the owners lived in the area and showed up in solidarity with the protest.

On one side of the street are the protesters, mostly African American, carrying signs, shooting photos, being interviewed by mostly white journalists. On the other side are the police, virtually all white, from a variety of police departments. A pack of five-o zip by in an SUV with an officer sitting on edge of the opened trunk, his feet dangling inches above the asphalt. People watch and wonder aloud what would happen if they tried to do that.

“We just want change,” 34-year-old Shirene said. “We know change may not come tomorrow. We know change may not come next week. We know it’s gonna be hard work to change but we’re willing to put that hard work in, we are. We’re tired of it.”

When asked how the community could bring about this change — or rather, how residents and police can work together to build a trusting and safe place to work and live — Shirene’s answer was simple.

“By doing what we’re doing now.”

Sitting on the curb in front of McDonald’s (which has been a haven for out-of-state journalists but has now begun closing early since one of its windows was broken), Shirene talks about what she’s doing — sitting in support of change.

“The world is watching us. The world is watching them,” she said about the police. “I can do this all day long… It takes dedication. It takes determination. It takes hard work. It takes faith. It takes love. It takes commitment. It takes respect. And we got that, but that’s not what the world is seeing.”

She added: “There’s some very smart people out here — kids, 7-year olds… but that’s not what you’re seeing. You’re seeing the ignorant fools that are breaking in for some Jordans.”

Those supporting police Officer Darren Wilson, the man accused of killing Michael Brown, have a similar complaint. Andy, a 34-year old St. Louis emergency medical technician and fireman, said that Officer Wilson’s presumed guilt is unfair

“I believe he was right in defending himself,” Andy said.

Andy, a Caucasian, admitted that racism still exists, but added that African-Americans exaggerate its impact. He tells a story of a fellow black firefighter who took a stuffed toy monkey, tied a strap to its neck then hung it in the locker room. Andy said his dark colleague then filed a complaint with a firefighter’s civil rights group, claiming that Andy hung up the monkey.

“Why did he do that? I don’t know,” Andy said, admitting that there might have been some underlying racial tensions already in place, and his colleague might have been acting out his frustrations.

The racial tension is real. Shirene tells a story about police beating her up and arresting her after she called them to report a car accident that wasn’t her fault. This happened a year before Michael Brown’s death. It seems that each protester has a similar story — each anecdote a piece of kindling, filling a tinderbox that ignited when police officials made error after error as people sought answers after Mr. Brown’s killing.

Edward, 25, was caught on camera hurling a tear gas canister after police shot it into the crowd. Rumors circulated that children were nearby and that he grabbed the canister out of instinct. In the photo, he’s wearing an American flag shirt. To prove it was him in the photo, he took out his camera to show a photo of the clothes he was wearing, covered in soot, surrounding a trash can.

The photo, taken by AP photographer Robert Cohen, has become somewhat of an icon of Ferguson’s struggle. The image shows Edward’s long dreadlocks illuminated from behind as the tear gas canister erupts with light and smoke. Behind him, a masked protester raises his arms and another seems to smile.

Edward, who also goes by Skeeda, was arrested that night. He didn’t want to talk about why he threw the tear gas or where he threw it (since the investigation is open), but he wasn’t shy about expressing his frustration with what’s taken place.

“I never woke up that morning feeling like I’m gonna go break the law,” he said. “I woke up and the police was just fucking with me for the last time… for doing something I have the right to do.”

His father was a victim of gun violence. He’s tired of it. He also wants change. But he’s also caught up in the system. His children, he said, keep him sane and give him a reason to live.

“When my kids grow up, I want them to be able to walk to the store… I want them to be able to feel free,” he said. “I don’t want them to look over their should or feel scared when they see the police.”

One of the most commonly cited complaints in person and on Twitter is that police officers don’t live in the community they patrol. In the past, there was more of a connection to police because they were neighbors of the people they served. Today, many people say that officers are disconnected from the people, and the drive to make arrests trumps the need to create community.

Tim, a white native of St. Louis, tells me that he doesn’t think anything can be done to heal the racial tensions.

“It’s always been there,” he said. Others, like Andy, say more dialogue is needed.

“We need to bring everyone to the table and figure this thing out,” he said. “Them being over there and us here isn’t gonna work.”